Parts of a Car Tire Assembly

Understanding the parts of a car tire assembly is key to maintaining vehicle safety and performance. From the tread to the inner liner, each component plays a vital role in how your tires grip the road, handle weight, and resist wear. Knowing these parts helps you make smarter maintenance and replacement decisions.

When you look at a car tire, it might seem like a simple rubber donut. But beneath that smooth, black surface lies a complex engineering marvel designed to handle thousands of miles, extreme temperatures, heavy loads, and unpredictable road conditions. The parts of a car tire assembly work together like a well-rehearsed team—each playing a specific role in keeping you safe, comfortable, and in control.

Modern tires are not just rubber; they’re high-tech composites of steel, fabric, and specialized compounds. Every component is precision-engineered to balance performance, durability, and fuel efficiency. Whether you’re driving on a dry highway, a wet city street, or a gravel backroad, your tires are constantly adapting. Understanding how they do that starts with knowing the key parts that make up a tire assembly.

In this guide, we’ll break down each major component of a car tire, explain how it functions, and why it matters to your driving experience. Whether you’re a car enthusiast, a new driver, or just someone who wants to make smarter tire choices, this deep dive will give you the knowledge you need. Let’s roll into the details.

In This Article

- 1 Key Takeaways

- 2 📑 Table of Contents

- 3 The Tread: Your Tire’s First Line of Defense

- 4 The Sidewall: Strength and Information Hub

- 5 The Beads: The Tire’s Anchor to the Wheel

- 6 Belts and Body Plies: The Tire’s Internal骨架 (Skeleton)

- 7 The Inner Liner: The Air-Holding Hero

- 8 The Shoulder: Where Tread Meets Sidewall

- 9 Conclusion: Why Knowing Your Tire Parts Matters

- 10 Frequently Asked Questions

Key Takeaways

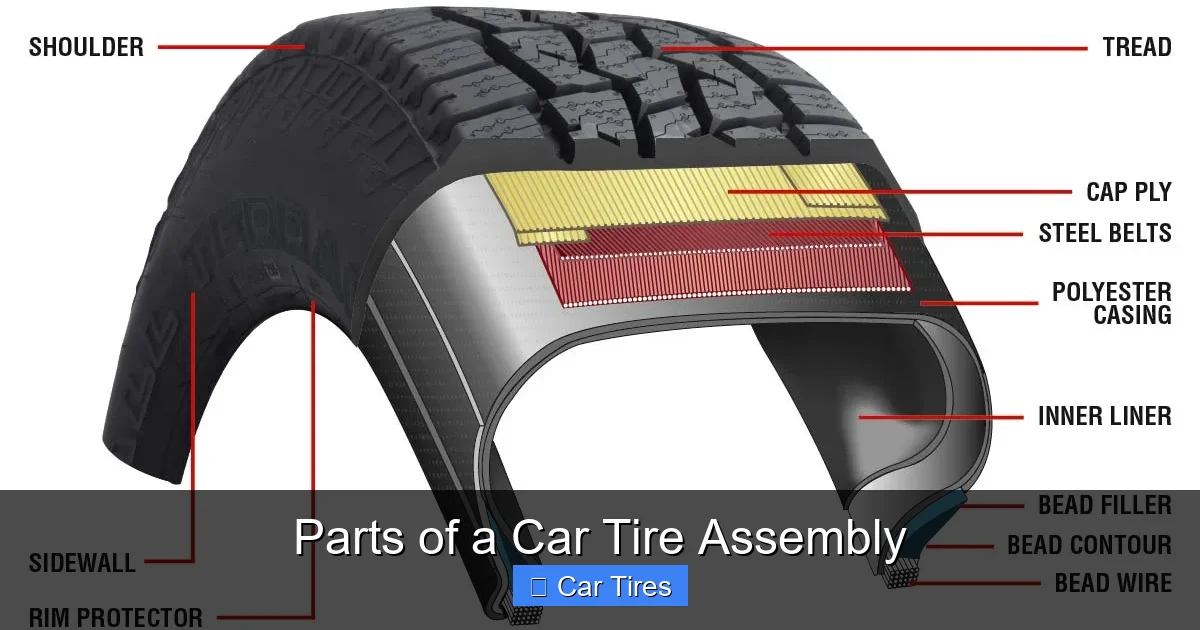

- Tread: The outermost layer that contacts the road, providing traction, water dispersion, and wear resistance.

- Sidewall: Protects the tire’s internal structure and displays important info like size, load index, and speed rating.

- Beads: Steel wire bundles that secure the tire to the wheel rim, ensuring an airtight seal.

- Belts: Steel or fabric layers beneath the tread that add strength, stability, and puncture resistance.

- Body Plies: Fabric layers forming the tire’s internal骨架 (skeleton), supporting its shape and flexibility.

- Inner Liner: A rubber layer that replaces inner tubes by holding air pressure in tubeless tires.

- Shoulder: The transition zone between tread and sidewall, aiding in heat dissipation and cornering stability.

📑 Table of Contents

- The Tread: Your Tire’s First Line of Defense

- The Sidewall: Strength and Information Hub

- The Beads: The Tire’s Anchor to the Wheel

- Belts and Body Plies: The Tire’s Internal骨架 (Skeleton)

- The Inner Liner: The Air-Holding Hero

- The Shoulder: Where Tread Meets Sidewall

- Conclusion: Why Knowing Your Tire Parts Matters

The Tread: Your Tire’s First Line of Defense

The tread is the part of the tire you see every day—the grooved, patterned surface that touches the road. It’s arguably the most important part of the tire assembly because it directly affects traction, braking, and handling. Think of it as the sole of your shoe: without good grip, you’re slipping and sliding.

What Does the Tread Do?

The primary job of the tread is to provide grip. On dry roads, the rubber compound and tread pattern create friction that helps your car accelerate, turn, and stop. On wet or snowy surfaces, the grooves (called tread voids) channel water away from the contact patch, reducing the risk of hydroplaning. This is why tires with deep, well-designed tread patterns perform better in rain and snow.

For example, all-season tires have moderate tread depth and siping (tiny slits in the tread blocks) to handle a variety of conditions. Winter tires, on the other hand, have deeper grooves and softer rubber to bite into snow and ice. Performance tires often have shallower tread but stickier compounds for maximum grip on dry pavement.

Tread Wear and Maintenance

Over time, the tread wears down. The legal minimum tread depth in most places is 2/32 of an inch, but experts recommend replacing tires when they reach 4/32 for better wet-weather performance. You can check tread depth with a simple penny test: insert a penny into the tread with Lincoln’s head upside down. If you can see the top of his head, it’s time for new tires.

Uneven tread wear can signal alignment issues, underinflation, or suspension problems. For instance, if the outer edges are worn more than the center, your tires may be underinflated. If the center is worn faster, they might be overinflated. Regular tire rotations every 5,000 to 7,500 miles help ensure even wear and extend tire life.

Tread Patterns: Symmetric, Asymmetric, and Directional

Tread patterns aren’t just for looks—they’re designed for specific driving needs. Symmetric treads have the same pattern on both sides and are common on everyday passenger cars. Asymmetric treads have different patterns on the inner and outer halves: the outer side focuses on dry grip and cornering, while the inner side channels water away. Directional (or uni-directional) treads have V-shaped grooves that point in one direction, optimized for water evacuation and high-speed stability.

Choosing the right tread pattern depends on your driving style and climate. If you live in a rainy area, a directional or asymmetric tire might offer better wet performance. For general use, symmetric tires are reliable and cost-effective.

The Sidewall: Strength and Information Hub

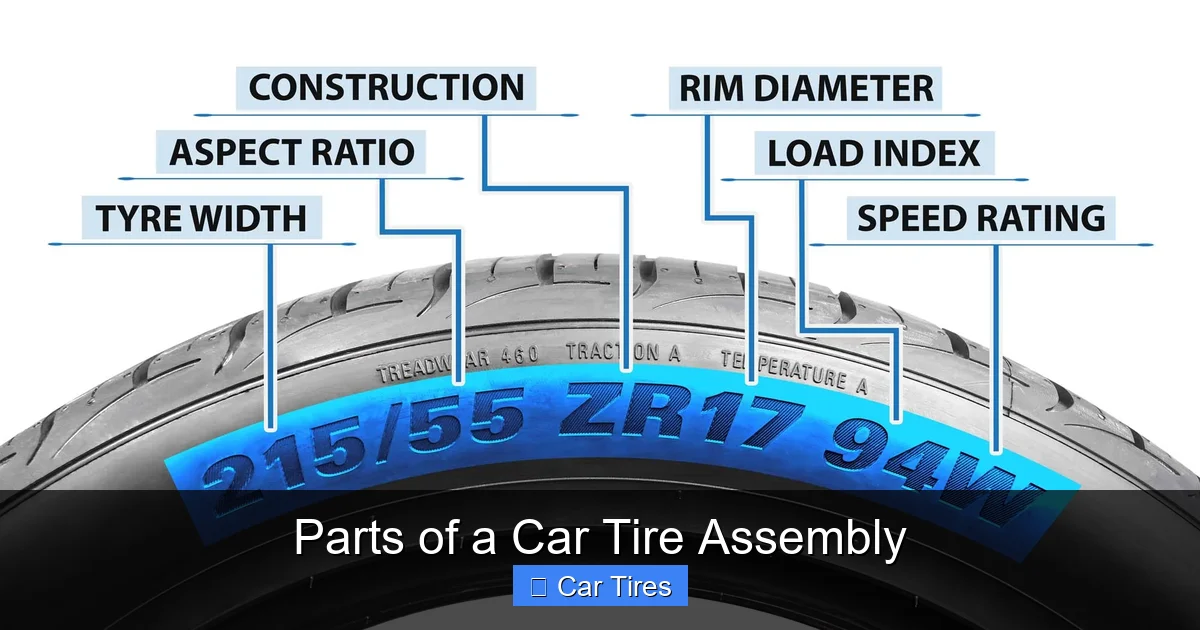

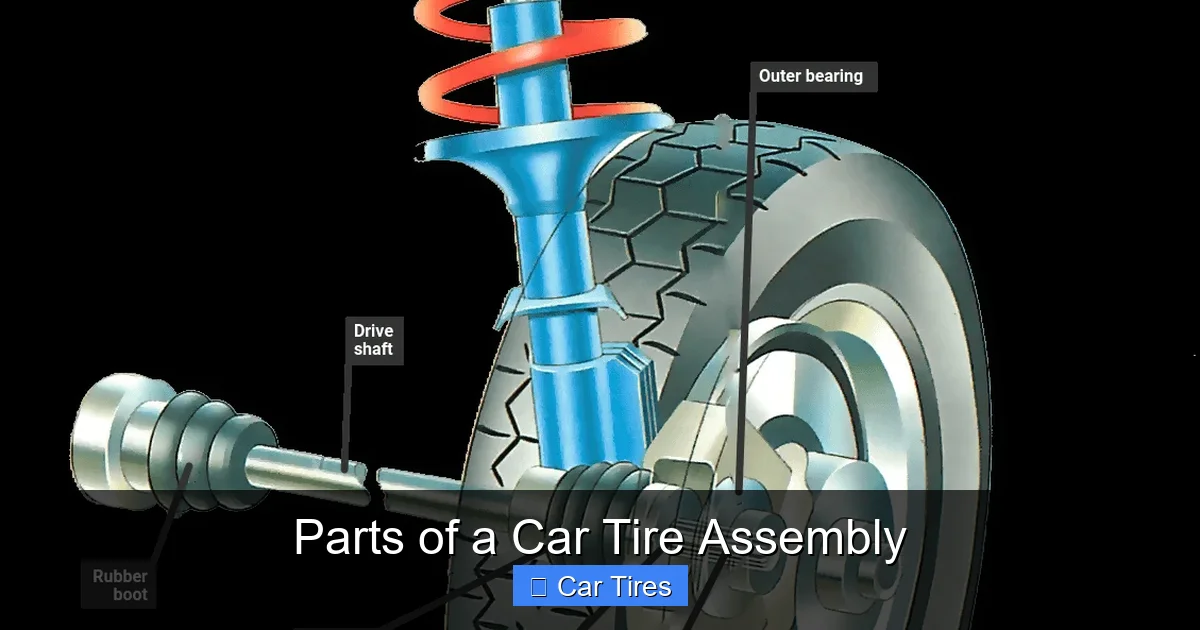

Visual guide about Parts of a Car Tire Assembly

Image source: tirehungry.com

While the tread grabs attention, the sidewall is the tire’s silent protector. It’s the vertical section between the tread and the bead, and it plays a crucial role in both function and communication.

Structural Support and Flexibility

The sidewall supports the weight of the vehicle and absorbs shocks from bumps and potholes. It must be strong enough to resist damage from curbs and debris, yet flexible enough to allow the tire to conform to the road. This balance is achieved through layers of fabric and rubber compounds designed to flex without cracking.

For example, low-profile tires (common on sports cars and luxury vehicles) have shorter sidewalls. This improves handling and responsiveness but reduces ride comfort because there’s less cushioning. High-profile tires, like those on SUVs and trucks, have taller sidewalls that absorb more impact, making for a smoother ride on rough terrain.

Information Display

The sidewall is also a treasure trove of information. Here’s where you’ll find the tire size, load index, speed rating, and manufacturing details. A typical marking might look like this: P215/65R15 95H.

– P = Passenger vehicle

– 215 = Tire width in millimeters

– 65 = Aspect ratio (sidewall height as a percentage of width)

– R = Radial construction

– 15 = Wheel diameter in inches

– 95 = Load index (maximum weight the tire can support)

– H = Speed rating (maximum safe speed)

Understanding these codes helps you choose the right tires for your vehicle. For instance, if your car came with H-rated tires (good for up to 130 mph), you shouldn’t replace them with T-rated tires (limited to 118 mph), even if they fit.

Sidewall Damage and Inspection

Because the sidewall is exposed, it’s vulnerable to cuts, bulges, and cracks. A bulge often indicates internal damage, like a broken belt or ply, and can lead to a blowout. Cracks, especially near the shoulder, may signal aging or dry rot. Regular inspections—especially before long trips—can catch这些问题 early.

Tip: Avoid parking too close to curbs. Even a small scrape can weaken the sidewall over time. If you notice any damage, have a professional inspect it immediately.

The Beads: The Tire’s Anchor to the Wheel

Visual guide about Parts of a Car Tire Assembly

Image source: lesschwab.com

Hidden from view, the beads are the unsung heroes of the tire assembly. These steel wire bundles sit at the inner edge of the tire and lock it onto the wheel rim, creating an airtight seal.

How Beads Work

Each bead consists of high-tensile steel wires wrapped in rubber and coated with brass for corrosion resistance. During installation, the tire is pressed onto the wheel, and the beads snap into the bead seat—a specially designed groove on the rim. Once seated, air pressure pushes the beads outward, locking them firmly in place.

This seal is critical. Without it, air would leak out, and the tire could detach from the wheel at high speeds—a dangerous scenario. That’s why proper mounting and balancing are essential. A poorly seated bead can cause vibrations, air loss, or even a sudden failure.

Bead Types and Materials

Most modern tires use radial beads, which are designed to work with tubeless rims. Some heavy-duty or off-road tires may use reinforced beads with additional wire wraps for extra strength. The rubber coating protects the steel from moisture and helps maintain flexibility.

When replacing tires, always ensure the new ones are compatible with your wheel type. For example, some aftermarket wheels have different bead seat profiles that may not work with standard tires. Using the wrong combination can lead to bead failure.

Installation Tips

Proper bead seating requires the right tools and technique. Mechanics use bead blasters—devices that release a burst of compressed air—to help the bead snap into place. If you’re changing tires at home, make sure the rim is clean and free of rust or debris. Lubricating the bead with soapy water (not oil-based lubricants) can ease installation, but avoid over-lubrication, which can cause slippage.

Never force a tire onto a rim with a pry bar. This can damage the bead or distort the tire. If the bead won’t seat, it’s best to seek professional help.

Belts and Body Plies: The Tire’s Internal骨架 (Skeleton)

Visual guide about Parts of a Car Tire Assembly

Image source: howacarworks.com

Beneath the tread and sidewall lies the tire’s internal structure—belts and body plies—that give it shape, strength, and durability.

Body Plies: The Foundation

Body plies are layers of fabric (usually polyester, nylon, or rayon) coated in rubber and layered diagonally across the tire. In radial tires—the standard today—these plies run perpendicular to the direction of travel, from bead to bead. This design allows the tread to stay flat on the road while the sidewalls flex independently, improving ride comfort and fuel efficiency.

The number of plies affects the tire’s load capacity and durability. Heavy-duty tires, like those on trucks, may have more plies to handle greater weights. Passenger car tires typically have one or two body plies.

Belts: Reinforcing the Tread

Belts are steel or fabric layers placed between the tread and the body plies. They act like a corset, stabilizing the tread and preventing it from distorting under pressure. Most tires have two steel belts, often wrapped with a nylon cap ply for added strength at high speeds.

Steel belts are strong, puncture-resistant, and help maintain tire shape. They also contribute to better fuel economy by reducing rolling resistance. Some high-performance tires use Kevlar or other advanced materials for even greater strength without added weight.

Radial vs. Bias-Ply Construction

Most modern cars use radial tires, where the body plies run radially (from side to side) and the belts are circumferential (around the tire). This design offers better handling, longer tread life, and improved fuel efficiency.

Bias-ply tires, with crisscrossing plies, are still used in some trailers, off-road vehicles, and vintage cars. They’re more rigid and can handle heavy loads, but they generate more heat and wear faster. Understanding the difference helps when choosing tires for specialized applications.

The Inner Liner: The Air-Holding Hero

In tubeless tires, the inner liner is a thin layer of airtight rubber on the inside of the tire. It replaces the need for an inner tube by sealing in the air.

Function and Material

The inner liner is made from butyl rubber, which has low air permeability—meaning it slows down air loss. Without it, air would seep through the tire’s porous materials over time. A good inner liner can keep a tire inflated for months with minimal pressure loss.

This is why tubeless tires are standard on modern vehicles. They’re lighter, easier to install, and less prone to sudden blowouts than tube-type tires. If a puncture occurs, the air leaks slowly, giving you time to pull over safely.

Maintenance and Leaks

Even with an inner liner, tires can lose air due to temperature changes, valve stem issues, or small punctures. Regular pressure checks (at least once a month) are essential. Underinflated tires wear faster, reduce fuel efficiency, and increase the risk of overheating.

If you notice a slow leak, it could be a damaged valve stem, a cracked rim, or a puncture near the bead. A professional can perform a leak test using soapy water to locate the source.

Run-Flat Tires and Reinforced Liners

Some high-end vehicles come with run-flat tires, which have reinforced sidewalls and inner liners that allow you to drive short distances (usually 50 miles) after a puncture. These tires are heavier and offer a firmer ride, but they eliminate the need for a spare tire.

The Shoulder: Where Tread Meets Sidewall

The shoulder is the curved area where the tread transitions into the sidewall. It’s a critical zone for heat dissipation and cornering performance.

Heat Management

During driving, especially at high speeds or during hard cornering, the shoulder generates significant heat. The design of the shoulder—including grooves, sipes, and rubber compound—helps dissipate this heat, preventing overheating and tread separation.

Performance tires often have reinforced shoulders with stiffer rubber to improve grip during aggressive driving. All-season tires may have more flexible shoulders for comfort and noise reduction.

Wear Patterns and Inspection

Shoulder wear can indicate alignment or inflation issues. Excessive wear on one shoulder may mean the tire is leaning due to a bent suspension component. Cupping (scalloped dips in the tread) can signal worn shocks or struts.

Regular inspections can catch these problems early. Look for uneven wear, cracks, or bulges in the shoulder area. If you notice any abnormalities, have your suspension and alignment checked.

Conclusion: Why Knowing Your Tire Parts Matters

Every time you drive, your tires are working hard—supporting your vehicle, gripping the road, and keeping you safe. Understanding the parts of a car tire assembly isn’t just for mechanics or car geeks. It’s practical knowledge that empowers you to make informed decisions about maintenance, repairs, and replacements.

From the tread that grips the asphalt to the beads that anchor the tire to the wheel, each component plays a vital role. Regular inspections, proper inflation, and timely rotations can extend tire life and improve performance. And when it’s time for new tires, knowing the differences in construction, materials, and design helps you choose the best option for your driving needs.

So the next time you glance at your tires, remember: they’re not just rubber circles. They’re sophisticated systems built for safety, efficiency, and reliability. Treat them well, and they’ll carry you mile after mile with confidence.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most important part of a tire assembly?

The tread is often considered the most important part because it directly affects traction, braking, and handling. However, all components work together, and a failure in any part—like the beads or inner liner—can compromise safety.

How often should I check my tire pressure?

Check your tire pressure at least once a month and before long trips. Temperature changes can affect pressure, and underinflated tires increase wear and reduce fuel efficiency.

Can I mix different tire types on my car?

It’s not recommended. Mixing tire types (e.g., all-season with winter) can affect handling and stability. Always use the same type, size, and brand on all four wheels for best performance.

What causes a tire to lose air over time?

Normal air loss occurs due to temperature changes, valve stem leaks, or tiny punctures. The inner liner slows this process, but regular pressure checks are still necessary.

How do I know if my tire beads are properly seated?

Properly seated beads create a uniform gap between the tire and rim. If you hear a loud “pop” during inflation or see air escaping, the bead may not be seated correctly—seek professional help.

Are steel belts better than fabric belts?

Steel belts are stronger, more puncture-resistant, and help maintain tire shape, making them ideal for most modern tires. Fabric belts are lighter but less durable, often used in specialty applications.